Osteoarthritis (OA)

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease that affects millions of people worldwide. The disease often causes pain, swelling, and stiffness, which can lead to immobility, difficulty with daily activities, and disability. Osteoarthritis currently is incurable, and researchers actively are trying to identify new treatments.

What is osteoarthritis (OA)?

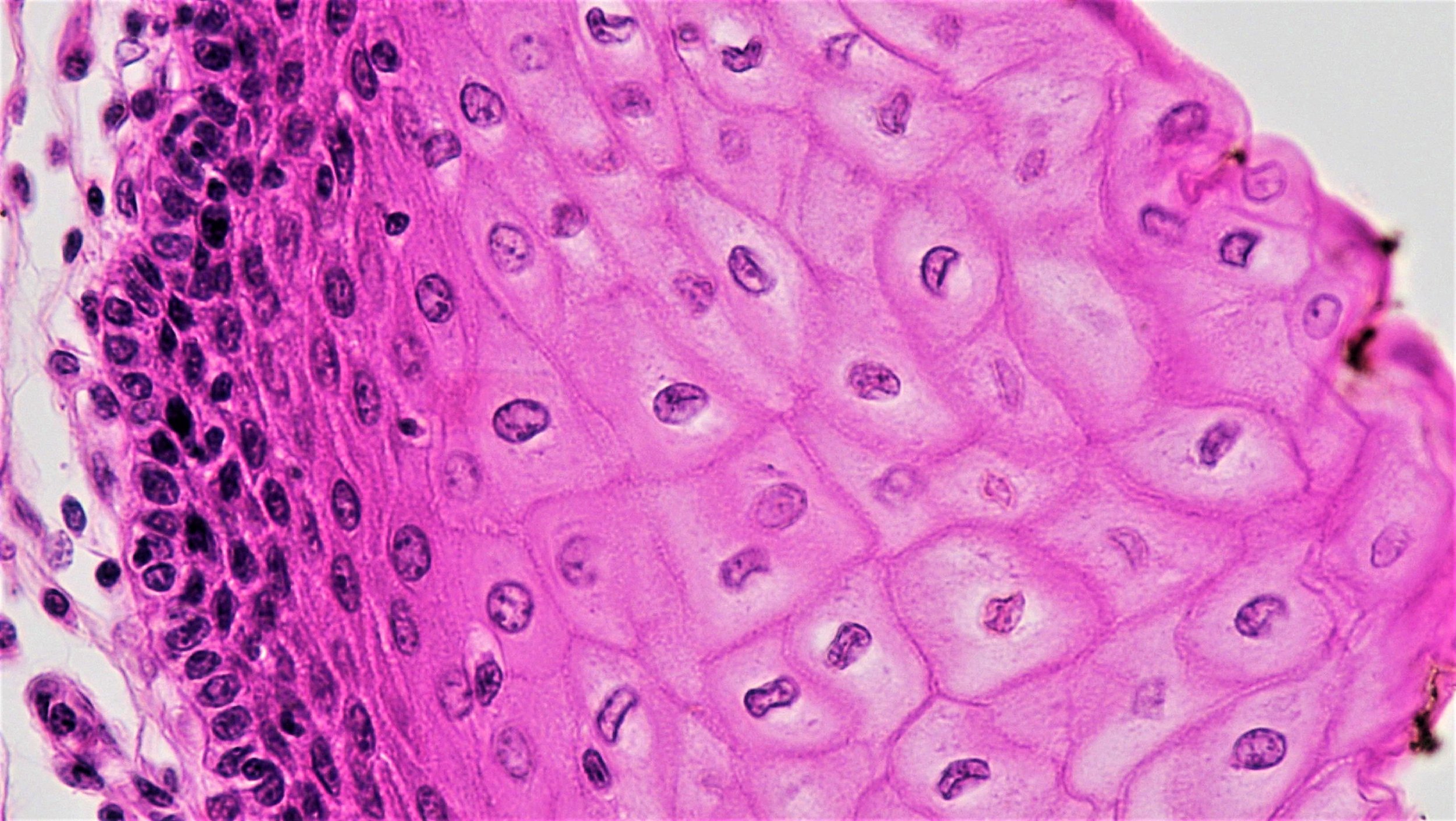

Osteoarthritis is a common, chronic, incurable degenerative disorder of the joints, the area of the skeleton where two bones come together. Over time, cartilage, the connective tissue that forms a protective cushion at the ends of the bones, wears down, tendons and ligaments deteriorate, and inflammation increases. When this happens, joints become painful and stiff. OA can occur in any joint, but is most common in knees, hips, spine, and hands.

There are multiple risk factors that lead to an increased likelihood of OA, such as advancing age, obesity, joint injuries, repeated stress, and genetic predisposition. OA also is more common in women. The specific genes that influence OA remain unknown, which substantially limits treatment options.

Many people do not experience pain during the early stages of degeneration and only find out they have the disease once it is widespread, irreversible, and visible by x-rays. Treatments exist to manage OA, reduce pain, and keep patients mobile, but OA cannot be cured.

How is osteoarthritis treated?

Osteoarthritis is one of the top causes of disability in older adults worldwide. Current treatment options aim to reduce pain and improve function.

One of the most important parts of any OA treatment plan is exercise. Movement can help increase muscle strength and reduce joint pain, stiffness, and the chance of disability. Exercise also promotes weight loss, which reduces stress on joints.

Patients with OA often are prescribed medicine to combat pain and inflammation. Medication can be taken orally, applied topically, or injected into the joint. Many patients experience short-term relief from anti-inflammatory therapies such as corticosteroid injections or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

In severe cases when there is serious damage to the joint and other treatment options have failed to relieve pain or disability, patients with OA may be treated with surgery. If the joint cannot be repaired through surgery, it may need to be replaced. Total joint replacements have excellent patient outcomes and prosthetics can last about 15 to 20 years.

How are stem cells used to understand osteoarthritis?

Scientists are in the early stages of using stem cells to better understand joint development and deterioration and to investigate new treatments. Stem cells can be used to study how joint tissues normally form, model how cartilage (the connective tissue that protects joints) breaks down, and attempt to make replacement cartilage tissue.

One challenge of this research is that cartilage does not regenerate after birth. Therefore, researchers must figure out how cartilage is formed prenatally. Scientists use factors identified in embryonic joint formation to turn pluripotent stem cells, cells that have the ability to become any cell in the body, into cartilage. After understanding how joints are formed during embryonic development, scientists can try to mimic this process using cells in the lab to repair damaged cartilage or by activating cells in the patient to form new cartilage. Scientists are actively trying to identify approaches that can safely and effectively repair damaged joints and alleviate symptoms.

Scientists also use stem cells to model disease. Modeling OA can help researchers understand what goes wrong during joint degeneration and identify new treatments that can repair this process. Cell samples from patients with OA can be used to make induced pluripotent stem cells, one type of pluripotent stem cell. These induced pluripotent stem cells will have the specific genetic makeup of the patient and can be directed to form cartilage that can be used to model OA, helping researchers understand the genetic basis of disease, potentially yielding patient-specific treatments.

What is the potential for stem cells to treat osteoarthritis?

Stem cell treatments could potentially help repair damaged joints in multiple ways, including modulating the immune response, delivering cells that can be directed to form cartilage, transplanting stem cell-generated cartilage, or stimulating a patient’s own cells for regeneration. Goals of these potential stem cell therapies include pain relief, inflammation reduction, and regeneration or replacement of joint tissues. While stem cell therapies may help OA patients in the future, at this time no stem cell procedures have been proven safe and effective through clinical trial, nor have they been granted regulatory approval. In order for stem cells to be used to safely treat OA, it is essential that potential treatments are thoroughly tested in robust, regulated, and controlled clinical trials.

Despite the absence of high-quality clinical trial data, many clinics currently offer “stem cell” approaches that have not been proven to be safe and effective for OA, and make claims that are not supported by sound, evidence-based science. These treatments generally use mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), which can also be referred to as mesenchymal stem cells. These cells, however, are often a mixed population of cells from blood, fat, and bone marrow, with little, if any, indication that they include live stem cells.

After being collected from a patient, these mixed populations of cells can either be injected directly back into the same patient, or grown in a laboratory and processed to select for a specific subpopulation before injection. Lab-grown cells have been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties and to stimulate other cells to improve tissue repair in certain early clinical studies. Clinical trials are ongoing to test the regenerative capabilities of these cells. Less is known, however, about the direct injection of mixed populations of cells from patient’s blood, fat, or bone marrow. These cells often are uncharacterized, and their identity and regenerative capacity are unknown. The biological properties and therapeutic potential of cells from both of these preparations are controversial and require substantial additional scientific research.

The potential to use these poorly defined cells for OA primarily has been explored to treat small, focal defects in the joint surface cartilage, and not for the more generalized cartilage loss and joint damage seen in osteoarthritis. Importantly, current approaches have not been shown to regenerate cartilage.

What is the clinical status of cell-based therapies for osteoarthritis?

There is a lack of clear support from high-quality studies, and a lack of consensus in the scientific and medical communities around many aspects of using cell therapies to treat OA, including when stem cells should be used, the ideal source of stem cells, and how they should be prepared, defined, or delivered. Despite the lack of strong and supporting evidence, “stem cell” injections, are being sold as a strategy to modify the joint or regenerate cartilage in patients with OA. These unregulated and unproven approaches are not only ineffective, but they can cause both physical and financial harm.

A study in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery recently performed a comprehensive literature review to identify all high-quality clinical studies that used cell therapy to treat knee OA. Of the over 400 studies they reviewed, the authors were only able to identify three studies that met their criteria for quality, none of which were a randomized clinical trial, the most rigorous, and “gold standard,” of clinical trials. The three identified studies included only a small number of patients and used different methodologies, which prevents direct comparison between studies. These studies, which examined cell injections to treat knee OA, showed modest improvements and a low number of serious adverse events, but due to the small numbers of patients, mixed methodologies, and a failure to test for a placebo effect, conclusions can’t be drawn at this time. The field needs standardized methods, properly controlled studies, and more robust clinical trials in order to determine if cell therapy is safe and effective for treating the disease.

Patients with severe pain who are unable to work, perform self-care, or even walk may explore alternative and/or experimental approaches to treat chronic pain or disability, or to avoid total joint replacement.

Patients who are exploring clinical trials should note that trial entry into common registries, such as ClinicalTrials.gov in the United States, does not mean that the studies have been peer reviewed, vetted, or endorsed by any governmental, scientific, academic, or regulatory body. To learn more about how to investigate whether a clinical trial is safe and legitimate, refer to our Patient Resources, including “Nine Things to Know About Stem Cell Treatments” and “Unproven Stem Cell “Treatments”.”

The effects and effectiveness of cell therapies for the treatment of OA in humans remain unproven and the scientific community cannot recommend them at this time.

Useful Links

July 2019